Shrinkwrap: Taming dynamic shared objects

Published 2022-03-14 on Farid Zakaria's Blog

This is a blog post of a paper I have submitted for a UCSC course project.

If you are interested in the code check out https://github.com/fzakaria/shrinkwrap

One of the fundamental data management units within a Linux system are the shared object files that are loaded into memory by dynamically linked processes at startup. The mechanism and approach to which dynamic linking is done has not changed since it’s inception however software has become increasingly complex.

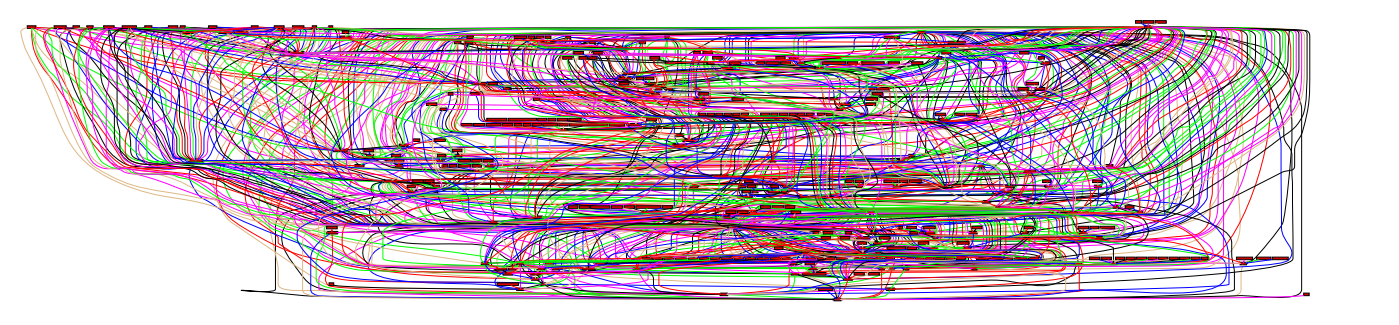

This is the full build and run closure for Ruby in Nix, which is a good visual depiction of the complexity.

The discovery of the needed dependencies can at most be controlled by small set of directory lists or typically rely on convention for discovery, better known as the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS).

The reliance on convention for discovery of shared objects while simple, has resulted in challenges when trying to rebuild solutions reproducibly and root cause discrepancies between machines – “It works on my machine but not yours”.

Novel new software packaging models have emerged such as Nix, Guix and Spack, that attempt to tame the chaos of dependency hell by eschewing all uses of the FHS and relying on explicit deterministic paths. These tools have made great strides in moving software packaging to becoming more reproducible but still exhibit certain flaws, specifically performance, as a result of building upon tooling that was designed for a different paradigm.

Shrinkwrap is a tool that attempts to overcome some of the performance limitations with how software may be packed in store-like models by freezing the dependencies directly on the executable.

For a different approach to this problem, check out this blog post by the Guix developers.

The number of dependencies needed for a particular binary transitively, and the RUNPATH can vary greatly. For instance, emacs lists 36 directories in it’s RUNPATH and requires 103 dependencies to be resolved.

The result is that the dynamic linker must attempt potentially 3600 filesystem operations (openat or stat) to resolve the needed dependencies every time the process is started.

🐌 This exorbitant cost can be made worse if the store itself resides on a shared filesystem such as NFS. 🐌

$ patchelf --print-rpath /nix/store/vvxcs4f8x14gyahw50ssff3sk2dij2b3-emacs-27.2/bin/.emacs-27.2-wrapped \

| tr ':' '\n' | wc -l

36

$ ldd /nix/store/vvxcs4f8x14gyahw50ssff3sk2dij2b3-emacs-27.2/bin/.emacs-27.2-wrapped | wc -l

103

💡 When faced with a recurring problem, often the solution is to cache the previous answer to avoid unnecessary work.

Shrinkwrap adopts this approach by freezing the required dependencies directly into the DT_NEEDED section of the binary by having it point to an absolute path. The

transitive dependency list is also lifted to the top-level binary to simplify auditing the required dependencies.

$ patchelf --print-needed /nix/store/zb2h75vbhg7w42b3f42bl0y2d4m0a4n3-emacs-27.1/bin/.emacs-27.1-wrapped

libtiff.so.5

libjpeg.so.62

libpng16.so.16

libz.so.1

libungif.so.4

libXpm.so.4

libgtk-3.so.0

libgdk-3.so.0

$ shrinkwrap /nix/store/zb2h75vbhg7w42b3f42bl0y2d4m0a4n3-emacs-27.1/bin/.emacs-27.1-wrapped -o emacs_stamped

$ patchelf --print-needed emacs_stamped

/nix/store/2nkjrh3za68vrw6kf8lxn6nq1dval05v-gcc-10.3.0-lib/lib/libstdc++.so.6

/nix/store/jvbyjnjh4w8qg7izfq4x5d2wy9lv9461-icu4c-70.1/lib/libicudata.so.70

/nix/store/2kzsm8hhc4lzji6g1ksav9bdjbbiyxln-libgpg-error-1.42/lib/libgpg-error.so.0

/nix/store/mpwncqr8fbqflmglkrxj7a288xdbymk3-util-linux-2.37.2-lib/lib/libblkid.so.1

/nix/store/8n6mjngkw6909rx631rzwby2rsdk0blf-libglvnd-1.3.4/lib/libGLX.so.0

/nix/store/8n6mjngkw6909rx631rzwby2rsdk0blf-libglvnd-1.3.4/lib/libGLdispatch.so.0

/nix/store/xlvnyyviqcjys8if5hgkyykgv7d10hb8-libdatrie-2019-12-20-lib/lib/libdatrie.so.1

/nix/store/2zl3dw54ysdf55hngapkkfhiw0w8c9gp-json-glib-1.6.6/lib/libjson-glib-1.0.so.0

/nix/store/30q5xa4pfbvic54nh68qn86w6kjki66i-sqlite-3.36.0/lib/libsqlite3.so.0

/nix/store/jvbyjnjh4w8qg7izfq4x5d2wy9lv9461-icu4c-70.1/lib/libicui18n.so.70

/nix/store/jvbyjnjh4w8qg7izfq4x5d2wy9lv9461-icu4c-70.1/lib/libicuuc.so.70

Applying Shrinkwrap resulted in a large reduction in syscalls, which equates to a 36x speedup. The absolute amount recovered may seem negligible however this unnecessary penalty is paid on every process invocation, and on every machine executing the binary.

| Program | Calls(stat/openat) | Time (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|

| emacs | 1823 | 0.034121 |

| emacs_stamped | 104 | 0.000950 |

The above was captured using

strace – strace -e openat,stat -c ./emacs_stamped --version

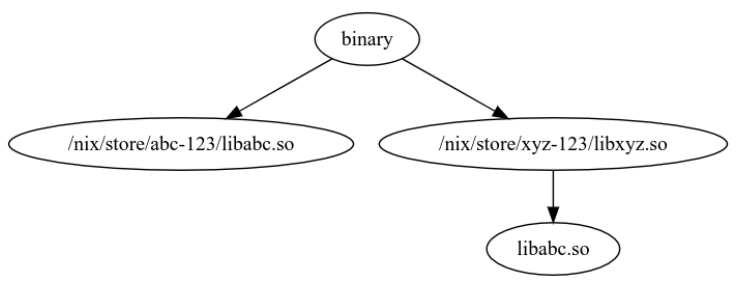

Shrinkwrap relies on the ability for a dynamic linker to deduplicate libraries with a common basename or whose soname (ELF header value) are the same. For instance in the below image, Shrinkwrap elevated libac.so to a direct absolute dependency of the binary, but relies on the dynamic linker deduplicating the resolution for libxyz.so which does not refer to it absolutely.

⚠️ This functionality currently does not exist in musl and only works with glibc. ⚠️

Please see this mailing list discussion for more details with musl.

Nothing in Shrinkwrap assumes any Nix specifics and it may also be integrated into other store-like systems as well such as Guix and Spack.

It is not yet integrated into Nixpkgs but I would love feedback. 😊

Philosophical Questions

Changing the needed dynamic dependencies to point to absolute paths, especially when those paths are immutable and content-addressable, may have philosophical and legal considerations for certain open-source licenses such as LGPL.

LGPL specifically mentions that only in the case of dynamic linking is the license not propagated over. Although these dependencies go through the process of being dynamically linked, the library they are linked to is effectively fixed.

Does this distinction blur the differentiation between static and dynamic linking?

What if the linker validated the content-address to also verify the library hasn’t been changed?

Additional investigation into the legal ramifications may be an opportunity for future work.

Improve this page @ e8a829c

The content for this site is

CC-BY-SA.